Stretching quietly across western and northern India, the Aravalli Hills and Ranges are among the oldest surviving mountain systems on Earth. Long before the Himalayas rose, the Aravalli had already shaped climate, water, soil, and life across the subcontinent. Today, however, these ancient hills stand at the center of one of India’s most complex environmental and legal conflicts—one driven not by nature, but by human definitions, fragmented governance, and unchecked extraction. This includes significant concerns surrounding Aravalli Hills Mining.

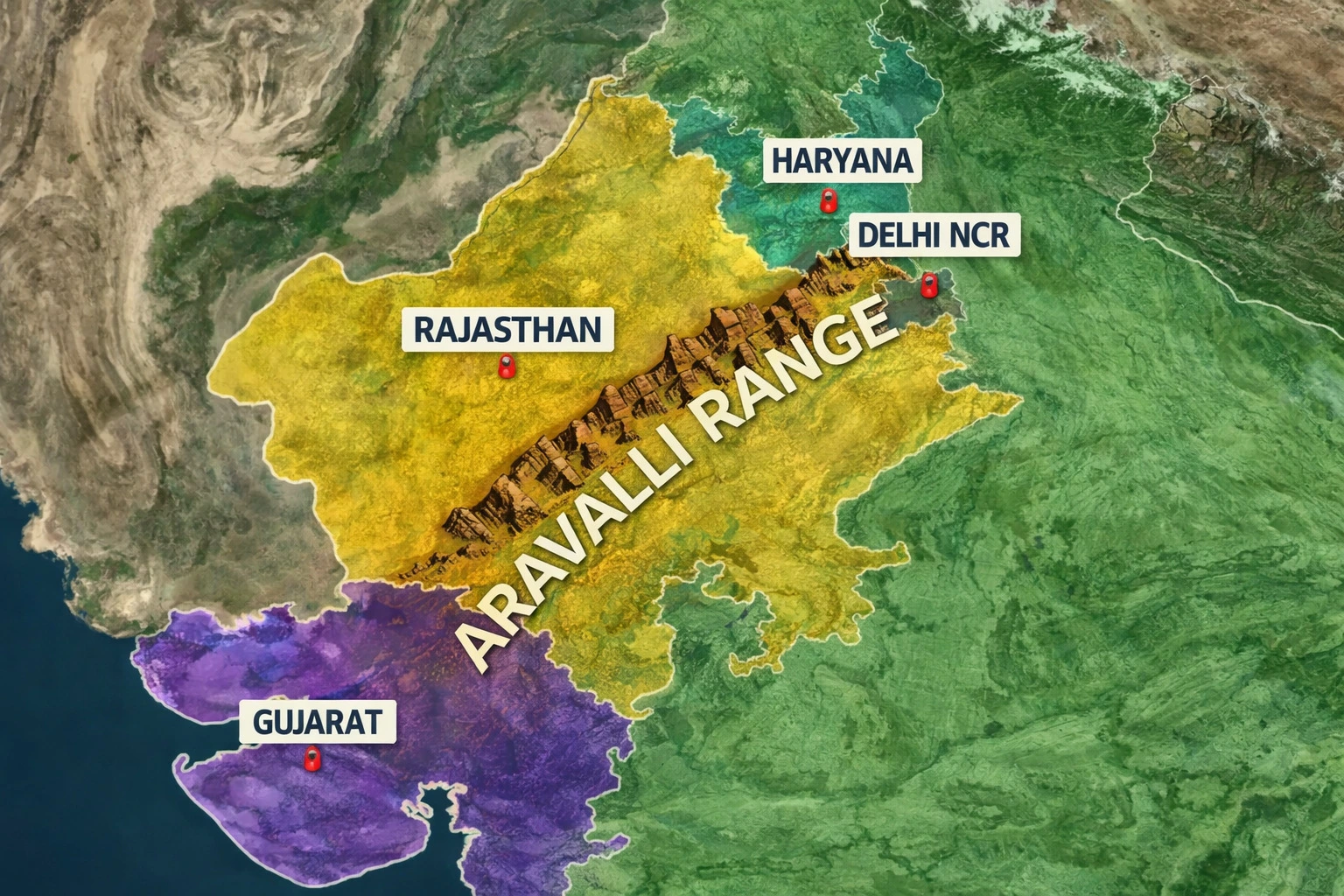

The Aravalli range runs for roughly 690 kilometers, beginning near Palanpur in Gujarat, cutting through Rajasthan, touching Haryana, and reaching into Delhi NCR. Despite this continuous geological identity, the range has been treated differently by each state it passes through. These conflicting definitions became the root cause of widespread environmental damage.

Four States, Four Definitions — One Broken Ecosystem

For decades, Delhi NCR, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat adopted their own interpretations of what constituted “Aravalli hills” or “Aravalli ranges.” In some regions, only prominent hill forms were recognized. In others, slopes, foothills, valleys, and buffer zones were excluded entirely.

This fragmentation created dangerous loopholes.

Areas that were geologically and ecologically part of the Aravalli were reclassified as “non-hill land,” opening them up to intensive mining, stone crushing, and metal extraction. What followed was not isolated development, but a cumulative collapse of ecological continuity—habitats broken apart, wildlife corridors severed, aquifers damaged, and forests stripped down to exposed rock.

Why the Aravalli Hills Mining Matter More Than We Think

Scientifically, the Aravalli ecosystem functions as a green barrier. It slows the eastward expansion of the Thar Desert, protects the Indo-Gangetic plains, and plays a crucial role in climate regulation across North India. This is not theoretical. Studies cited by the Supreme Court confirm that degradation of the Aravalli accelerates desertification, dust storms, and heat extremes across Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi NCR.

Hydrologically, the range is even more critical. The Aravalli recharge aquifers that feed major river systems, including the Chambal, Sabarmati, Luni, Banas, and Mahi. Mining that cuts below groundwater levels does not merely remove stone—it permanently fractures underground water systems.

Wildlife, Biodiversity, and Silent Loss

Ecologically, the Aravalli landscape hosts 22 wildlife sanctuaries, four tiger reserves, and globally significant wetlands such as Keoladeo National Park, Sultanpur, Sambhar, Siliserh, and Asola Bhatti. These areas form an interconnected mosaic of dry deciduous forests, scrublands, wetlands, and grasslands.

Illegal and unregulated mining has fragmented these habitats beyond visible repair. Large mammals lose corridors, reptiles lose nesting grounds, birds lose wetlands, and endemic plant species vanish without documentation. Biodiversity loss here is not dramatic—it is silent and cumulative, making it easy to ignore until recovery becomes impossible.

The Turning Point: The Central Empowered Committee (CEC)

The environmental breakdown of the Aravalli eventually reached India’s highest constitutional forum through T. N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India, a landmark forest conservation case that has shaped Indian environmental law for decades.

To monitor compliance with Supreme Court orders, the Court constituted the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) in 2002. Its mandate was clear: investigate violations, review mining and encroachment, and advise the Court on conservation failures.

By 2024, the CEC identified a core issue behind rampant illegal mining—the absence of a uniform, scientific definition of the Aravalli Hills and Ranges. States were exploiting ambiguity. The environment was paying the price.

Supreme Court Intervention and a Uniform Definition

In response, the Supreme Court of India, through a Special Bench led by Chief Justice B. R. Gavai, ordered a decisive correction.

Relying on expert institutions such as the Forest Survey of India and the Geological Survey of India, the Court acknowledged that inconsistent definitions had enabled ecological destruction. It accepted the CEC’s findings and directed the Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change to implement a uniform, science-based approach across all four states.

Crucially, the Court ordered:

1.No new mining leases in Aravalli areas until scientific assessments are complete

2. Strict prohibition of mining in core, inviolate, and wildlife-sensitive zones

3. Closure of mines damaging aquifers or operating without statutory clearance

4. Preparation of a comprehensive Management Plan for Sustainable Mining (MPSM) for the entire Aravalli range

These directions mark one of the most significant environmental interventions in recent Indian history

Human Impact: Beyond Forests and Files

For local communities, the Aravalli crisis is not abstract. Depleted groundwater affects drinking water and agriculture. Dust pollution raises respiratory illness. Loss of grazing land impacts livelihoods. Environmental collapse here directly translates into human vulnerability.

The Court recognized this balance—rejecting a blanket mining ban to avoid illegal operations, while insisting on scientific limits that protect long-term ecological and human security.

An Ancient Range, A Modern Responsibility

The Aravalli are estimated to be over 1.5 billion years old—older than most life forms on land. Their value cannot be measured in minerals alone. They regulate climate, store water, host biodiversity, and protect millions of people from desertification.

What is at stake now is not just conservation, but continuity. Once fractured beyond recovery, ecosystems like the Aravalli cannot be rebuilt within human timescales.

The Supreme Court’s intervention offers a rare moment of course correction. Whether India seizes it will determine if the Aravalli remain a living mountain range—or survive only as a name on old geological maps.